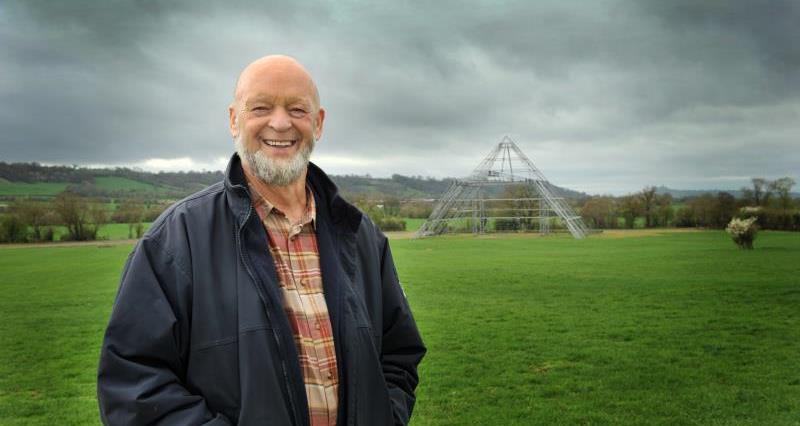

Michael Eavis invited the NFU’s #studentfarmer magazine to experience Glastonbury Festival as you’ve never seen it before. Victoria Wilkins reports...

I’ll tell you what you’re not thinking of: a 900-acre dairy farm that’s working flat out behind the scenes.

When the camera crews descend and the festivalgoers pile in, it couldn’t get farther from the serene, blissful quiet that the countryside has to offer. And by then it’s all too easy to let the images of a cider can floating down a man-made mud river take over.

We’re at the blissful quiet stage when we arrive at Worthy Farm one Friday morning in April. We’re greeted by a yard full of Land Rovers, in several different colours, and a bar with a single tap of Guinness on. I’m later told this isn’t how they pay the staff at Glastonbury, although I’m pretty sure they wouldn’t turn down the offer.

We’re at the blissful quiet stage when we arrive at Worthy Farm one Friday morning in April. We’re greeted by a yard full of Land Rovers, in several different colours, and a bar with a single tap of Guinness on. I’m later told this isn’t how they pay the staff at Glastonbury, although I’m pretty sure they wouldn’t turn down the offer.

After looking forlornly at the Guinness tap for too long we’re ushered in to an office and wait in the lounge like we’re waiting for a job interview, and the nerves set in. Every journalist gets them, and before long you forget your questions and yep – there we go, I’m fumbling around in my bag reminding myself what I’m supposed to ask.

We can hear Michael’s voice – it’s a distinctive Bristolian twang that I’ve heard on the radio countless times before. You know what it sounds like – you’re probably imagining it in your head as you read.

Over the course of the next five minutes, we’re in front of Michael who’s responding to fan mail – a daily ritual – and he’s asking if me and the photographer are in a relationship. Not awkward at all. After a silence, he gets back to his fan mail, answering local schools, charities and event organisers, sharing a hearty, infectious laugh that gets us all going.

To set the scene, he’s wearing a pair of knee-length shorts, a Barbour jacket and a deerstalker hat.

Before long he takes us on a tour of the office building – which is covered in various festival artwork – including a frame filled with wristbands from the year dot.

But he’s not that bothered about the office. He wants to get down to the real stuff – the farm.

“Shall we get in the Land Rover and see the cows – that’s good, isn’t it?” he asks, and we pile into the red Land Rover parked outside and begin our journey around the farm.

I thought this was a dairy farm – anyone would be mistaken for thinking otherwise – sheep litter the green pasture like they own the place, and there’s several thousand of them.

“The sheep are doing a good job, aren’t they?” he asks.

“We bring the sheep in during the winter months to clean up all the pasture. They eat the grass right down in preparation for the cows.”

Michael has a partnership with a local farmer who moves his entire flock of sheep onto the land from the day the cows are housed in winter, until the end of April. They eat away all the dead grass, allowing for regrowth, and then by the time they’re moved off the pasture the cows come out of the shed to a three-course meal waiting for them.

“We rotate the sheep around to graze the grass down,” he says as we’re sitting at the top of hill looking out across the farm, the land dotted with white splodges. It’s not the end of April yet, and his cows are still housed inside the Mootel – a luxury cow shed that the cows call home. Rumour has it that Michael used to play the Kinks to soothe the cows.

But the herd doesn’t come out as soon as the sheep are moved on – no. Everything is routinely managed in order to make sure the grass is ready for the festival.

“As soon as the sheep are moved on, we harrow all the land, spread the slurry and then the rain comes,” he says. Michael’s nodding – I get the impression there is never, ever any doubt of the rain coming in Pilton.

“Once we’ve got the grass, we cut all the silage and the cows are out at pasture in certain fields. So by the time the festival comes all of the fields are freshly cut and ready for the people to come.”

It’s a clockwork process – if anything runs over, or under, it could compromise the preparation time the festival has. And with over 400 workers descending on Worthy Farm in the run up to the event, everything has to run on time.

And up until four weeks before the festival, the cows are grazing in the fields – including the one that we’re standing in now that’s got the bare bones of the Pyramid Stage in it. I may have got a little too excited that Pharrell Williams has stood where I’m standing right now.

For those of you that want the inside scoop about what the backstage area at Glastonbury looks like: there’s a massive oak tree smack bang in the middle of the stage area, and it’s full of owls. Just imagine Kim Kardashian last year with owls – I dare you.

This stage is the fourth one they’ve built – and thankfully due to health and safety it’s not held up by the farmer’s friend – baling twine – which Michael says has saved them more than once.

He knows Glastonbury has got a reputation for being muddy, but a whole eight months after the festival looking at the field you wouldn’t have guessed a thing.

“We’ve got a name for being muddy – we’re not that bad,” Michael says.

“As a farmer you’re used to it. We try and build up the ground for rainwater flow so when it does rain, it forces the water down the ditches.

“That way the cows can go out to graze once the festival clear up has finished until the end of October.”

That’s when I go from talking about mud to talking about the likes of Kanye West. I ask him if he gets much say in the band choices with a raised eyebrow.

That’s when I go from talking about mud to talking about the likes of Kanye West. I ask him if he gets much say in the band choices with a raised eyebrow.

“I hope so, I pay for them,” he says, and there it is again, the infectious warm laugh that we’ve heard the entire journey. He tells us that his team are always looking for bands around the UK, going to gigs and watching them perform.

They then list all the ones they like, and the booking starts. I’m guessing no one ever says no to performing at Glastonbury Festival.

But it’s important that the people coming to the festival – both performers and spectators - know about the working farm. Everywhere you look festivalgoers are reminded to ‘Love the farm, leave no trace’ and the milk from the dairy, and other local ones, are sold on-site for £1 a carton. The tractors get involved, selling milk off the back of a wagon to bleary-eyed partiers too. Everything is brought back to the fact that once those people have gone, work resumes for the farm.

It’s about now that I take you back to that surreal sensation I had when I first set foot on Worthy Farm, and I can confirm it’s probably just about gone. Now all I’ve got left in me is the sheer respect for the people that carry out the job of organising the festival, and looking after the farm.

One thing for sure – one couldn’t work without the other. So next time you’re watching Glastonbury on TV spare a thought for the farm that’s making it all possible – and for the cows that have got to graze on the fields that are full of tents.

:: This article first appeared in the NFU's multi-award-winning #studentfarmer magazine. The magazine is for the next generation of British farmers and growers and is distributed at universities and colleges.

Click on the cover image below to read this issue along with the latest edition.