Last week, I had the opportunity to visit the Syngenta Innovation Center in Ghent, where RNA-based biocontrols are being developed as an option for future crop protection.

This visit was my first detailed introduction to this technology and what struck me most was the huge potential of RNA-based biocontrols to provide a range of highly-targeted crop protection products. This technology can be tailored to produce crop protection tools that control single pest insect species. This high level of selectivity means the products are also developed to be safe for key beneficials.

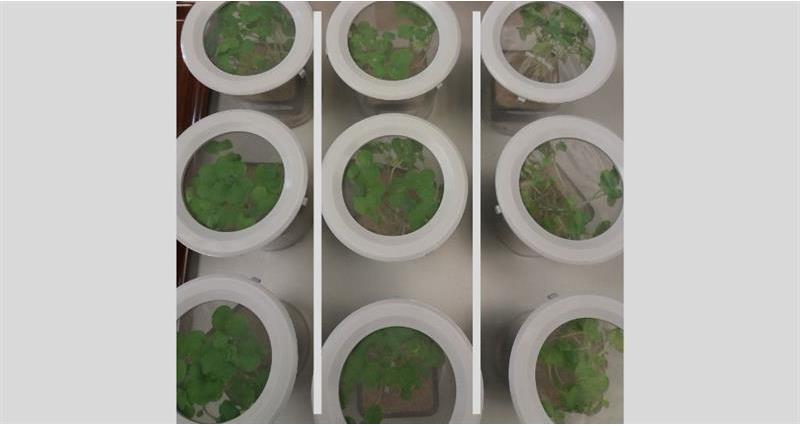

Picture shows (L-R) untreated oilseed rape seedlings with no flea beetles, seedlings treated with RNA-based biocontrol and exposed to flea beetles, seedlings with no biocontrol and exposed to flea beetles.

It offers huge promise, but the technology of RNA-based biocontrols also faces some tough challenges. The first is that it’s complex – starting with the challenge of explaining how it works, which I’ll try to do as simply as I can.

We know plants and animals are made from recipes contained in DNA. DNA provides the codes to produce the proteins that are the building blocks of cells and the basis of metabolic pathways. But DNA is like the complete cookbook containing all the recipes an organism needs – and it’s way too big a book to handle when all you want to do is make just one recipe. And you don’t want to rip pages out of the cookbook. So what you do is make a copy of the section that contains your recipe – and in the cell that copy of the DNA section containing your recipe is called messenger RNA (mRNA). Cells then read the instructions in the mRNA to make the relevant proteins – this step in the process is called translation.

At some point in evolution, viruses saw the opportunity to high-jack this process, realising that if they could inject their own genetic material into the cell, they could fool the cell into picking up their recipe, replicate it and produce the proteins to assemble multiple virus particles. So cells had to develop a defence against this – a way of inhibiting viral gene expression, or ‘turning-down’ the translation process – and this process is called RNA interference (RNAi). When this natural RNAi process is triggered, new small RNAs are produced that code for enzyme complexes that degrade the unwanted virus or mRNA, thereby decreasing its activity by preventing translation.

This natural process of RNA interference is being used in the medical field to fight diseases, and it can be used as the basis of RNA-based biocontrols for crop protection. To put in a nutshell many years of research and development, the first step involves identifying a target RNA sequence for your pest insect species, which could be unique to that species, or you could choose a sequence shared by a number of pest species. The next step involves designing and producing very specific double stranded RNA (dsRNA) that, once in the cells of your target pest, codes for the enzyme complex to degrade the target mRNA, which turns down it’s translation and protein production, slowing the relevant metabolic process, and controlling your pest insect.

The next challenging step is developing a production system that meets all the regulatory and product safety requirements, but also delivers high amounts of quality dsRNA material at an affordable price. Because it is this dsRNA that is the active ingredient of your control product, which will be sprayed onto the crop and ingested by your chewing or sucking insect pest. The inherent nature of RNA is that it rapidly degrades. While this is an advantage from an environmental and safety point of view, it makes formulating RNA-based biocontrols with short-term stability another challenge.

As a technology, RNA-based biocontrols are still in the development phase. It could be 8-10 years before the first products are on the market. Given the potential of RNA-based biocontrols and the rapidly dwindling toolbox of current crop protection options, this timescale will feel too long for some. Part of the issue is the length of time it takes to get new products through the EU regulatory process – a factor that frustrates the delivery of all new biocontrol technologies. They all fall under the plant protection products regulation 1107/2009, which applies a slow, one-size fits all approach that stifles the availability of safer, more effective and lower risk products.

The last challenge the RNA-based biocontrols will need to tackle is ensuring that this innovation meets consumer expectations and society views about agricultural technology. Going forward, as well as meeting the expectations of farmers in delivering safer, more effective and lower risk control of pests, future control technologies will also need to meet the expectations of the farm’s customers and consumers.

RNA-based biocontrols offer huge potential as future sustainable crop protection products, and while farmers will be hoping for their speedy arrival, there are still several years of development, regulation, open communication and conversation to be had before they become available.

Read more: